<an a to z of cult speak>

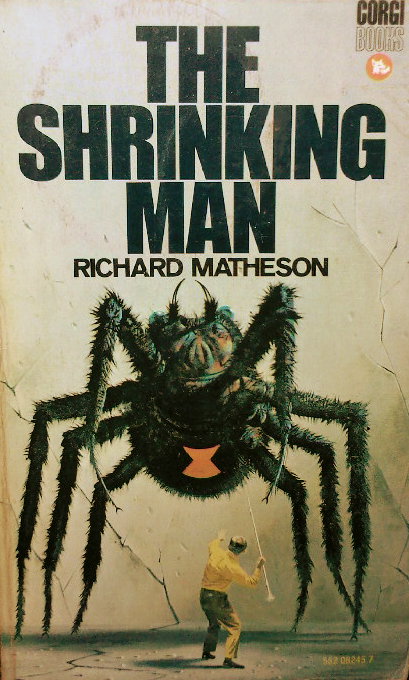

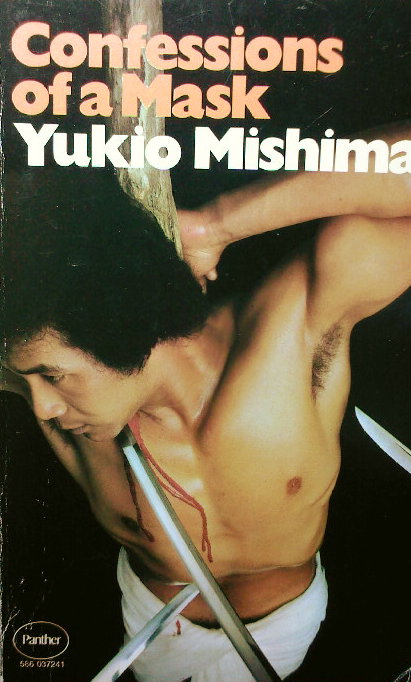

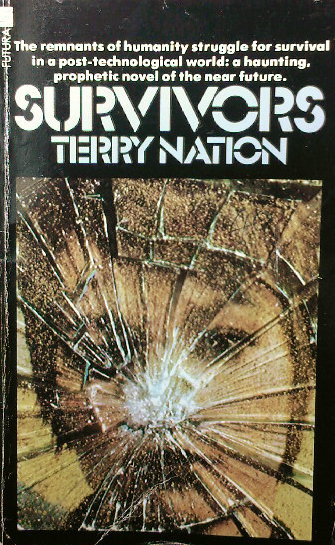

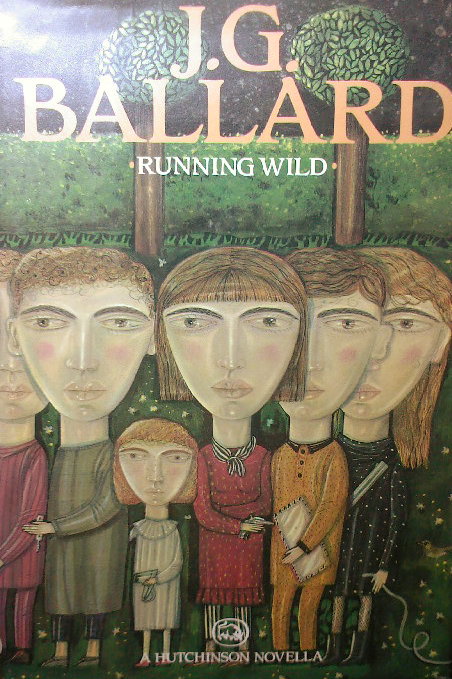

Androcentric: cult fiction has tended to be guy-centred partly as a response to shrinking masculine space in real life. Think Iron John (Robert Bly) for men beating their chests deep in the woods. Back in the 1950s gender space was clearly demarcated – the cellar, for example, the location where Scott Carey, diminished in size, fought and defeated the feminine other embodied by the inch tall Black Widow spider (Richard Matheson, The Shrinking Man) Ballardian (adjective, named after the author) is the mental awareness of something very sinister lurking beneath the veneer of consumer (and often suburban) normality Cut Up: borrowing from the Surrealist painter, Bryon Gysin, William S Burroughs used random combinations of text found in newspapers and books to bring new texts into being. Musician and artist, David Bowie, borrowed the technique from Burroughs, using it to give voice to his pop character Ziggy Stardust (see BBC Omnibus programme Cracked Actor)Die Young and attain cult immortality, if you believe the many populist books on ‘the ones that burn’ (Malcolm Lowry). Yukio Mishima was impelled towards death, despite a paradoxical attitude to body cult. Thomas Chatterton, the boy poet, was immortalised by the painter Henry Wallace as a suicidal loner. Death by your own hand isn’t a fool proof formula though. The rising young America writer, Weldon Kees, disappeared on the Golden Gate Bridge, never to be heard of again … or about, for that matter. Ecotopia ‘was the first attempt to portray a sustainable society,’ insists Ernest Callenbach, the author of the 1975 novel. ‘This more than its modest literary merit, explains its durability,’ he confesses. It’s certainly the case that there is no shortage of eco cults today. Even Terry Nation’s cult 1970s TV show Survivors – a green-tinted view of post apocalyptic